This summer, my skin turned into the flimsy flesh of anchovies. Silver, supple, slippery. I was more curious, than alarmed. At twenty-nine, women can discern such intimate bids for attention; when the body is so body, it beckons a form of noticing we usually reserve for; or seek from, others. My curiosity was that of a child at a fair; shuffling between a maze of adult calves, yanking at the hems of a coat, yearning for a grown-ups’-view of the world. (Another feature of the late twenties; being both, a child eager to see the pointy tips of structures, an adult crushed under their plinths.) That anxious tug, is political; drawing attention towards the margins of one’s body, vibrating with the most democratic demand of all: the right to be noticed, held; lovingly, and without persecution.

My favourite micro-genre of reading in this phase of life, is women writing about the dangerously lovely work of living. Memoirs, autofiction, essays; the whole platter. Finding grammar for what seem, at first glance, my most private and peculiar emotional states; in the words of women who have painstakingly inhabited and articulated them, is the truest feminist gift. The gift of a second, third, even fourth glance. The gentlest of invitations- There is room for you at our table, pull up a chair, darling.

The personal is political; yes, and it is a party.

In A Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone, Olivia Laing writes about carrying her lonely self in New York; a city where it is near impossible to be alone. Having moved countries for love, and finding herself immediately heartbroken, she writes movingly about encountering and learning pieces of herself, in and through, art and their artists.

A needling shame about the thinness of her life, as if she were “wearing a stained or threadbare piece of clothing;” the belief that her state was “down to some grave and no doubt externally unmistakable failing” in her person, and the tonal oscillation between “discomfort to chronic, unbearable pain,” Olivia writes out her loneliness in such fleshy detail, it makes me wonder if my own feelings are entirely loaned. And yet, I experienced them first-hand.

Like Olivia, I too indulged in a “false spring of desire,” with a man who departed from my life as swiftly as he arrived; leaving a haunting afterglow of an “alternate reality of accomplished love.” Olivia’s heart broke in a New York hotel room, and mine in the Leith heart of Edinburgh. She wrote about not crying often in the days following her breakup; but breaking down when she “couldn’t get the blinds closed”- she couldn’t bear the thought of her neighbours looking in and seeing how small and lacking her life was. I thought of the time that I woke up to brittle brown shards and blots bleeding into the cerulean lilies on my sheets, from the hot chocolate I had taken to bed but forgotten to drink. The starchy stains mocked my wholeness; this is what it has come to, outlining my failure at keeping my sad body clean. I cried oceans into the lilies until they wilted.

The kernel of “unmistakable failing” which took seed in Olivia as a “consequence of being so summarily dismissed” after her lover “changed his mind, very suddenly,” also sprouted in me; as I went over my own summary dismissal. The impatience to meet, the cool pulling away of his hand as I reached for it, the kind; rehearsed delivery of an unkind decision- this has been great, but I don’t think we are right for each other.

Both Olivia and I found ourselves “unexpectedly unhinged” by the pace of romantic arrival and departure; and both decided, in the first instance, that we were responsible for the “unappeasable abyss” we were drowning in. That we had made our own bed, and spilled hot chocolate all over it. Olivia terms her decision to move from England as “a hare-brained plan.” I wore his critique that I had failed to “protect my heart.” And yet, she did not follow a man. She opened a door in hopes for a life with love. I did not protect my heart. I was more encouraged than threatened by the possibility of new love. In the end, our hope was bigger than the men we draped it around.

A broken heart, I have come to learn, is a heart taken off its hinges. The boreholes are still there, awkward physical reminders that you planted a door to let someone in, unaware that doors are also apertures for leaving.

The structuration of romantic bliss in binary opposition to women’s appetite for professional distinction, is often narrated as a regrettable condition, rather than a structural violence in need of redress. In her book, Olivia writes about Edward Hopper, a renowned realist painter of the 20th century. She discusses the breadth of his work, but what stirs my curiosity is the seething presence of his wife, Jo, also a painter; in his life and work. Posing for his paintings; keeping a log of his work and their marriage, recording each sale, being a “consummate interrupter” filling in the gaps of his reticence in interviews; hers is the life, that I am drawn to.

When asked if loneliness was a consciously chosen theme in his paintings, Edward Hopper responded, “The interior is my main interest.” I spent time with his work, sliding between tabs, gazing at the women in them, looking out; often through glass, at once with the world and without. I paid attention to their silhouettes, searching for Jo, the sole model for almost all of his work. I then tried to look for Jo’s work; of which there is very little available, courtesy the Whitney museum, which decided to discard most of it after her death. The only recognition they afford her, is in and as Edward’s interior; as his milieu. Reading about the dwindling of Jo’s “much fought for, much defended” artistic career, after moving into her husband’s studio, leaves a metallic aftertaste. A tale as old as time.

Stories have the teeth that tales lack. In an article for The Paris Review, Sarah McColl, details how Jo put in a word for her husband with the curators of the Brooklyn Museum, a turning point; which leads him to sell his first painting in ten years, followed by a show given to him by the gallery. The story of his rising success and the diminution of her artistry to the status of a lady flower painter (as if there could ever be more urgent art than women and their flowers!), is incomplete. There are diary and interview records of Edward, expressing his sustained disapproval of his wife’s art, and of Jo’s unrelenting solidarity to his- “if there can be room for only one of us, it must undoubtedly be he. I can be glad and grateful for that.”

Jo is locked out of the room she planted doors to.

Exclusion is an ever-present risk to relating; made bearable only, by the promise of forging new intimacies. The belief that if we turned towards someone at just the right angle, their light would refract and confirm our surfaces. In loneliness, it is that belief in one’s density; the ability to absorb another’s light when it bends towards us, which is shattered. At an academic conference; shuffling between formally dressed, lanyarded bodies; seeking to both distinguish themselves from, and merge with me; the pressing up-closeness without a glint of intimacy; dizzied me. I noticed anxiety gather around my feet, closing in; what Olivia describes as a feeling “of being walled off or penned in, combined with a sense of near-unbearable exposure.” I changed angles constantly, and yet the light kept skidding off my smooth, slippery surfaces.

Exposure is the very currency of an academic career. The craving and the cost. Mid June, the Hilton in Glasgow felt like an overstretched membrane filled with vibrating atoms, drunk on discourse. The asking of brief life summaries by colleagues; eyes roving to make sure there wasn’t another more interesting person they needed to shift their already overextended attention to, conversations beginning over sponsored coffee and ending with the promise of more caffeine: the ritual demands of hyper-professional academic gatherings felt unbearable to me. Like Olivia, I was craving to be touched; and yet my instinct about being entirely transparent, made me terrified of contact, just when it was most required. I found myself imagining reaching out and touching the shoulder of complete strangers, and running off at tearing speed while they congratulated me for a recent publication. So much exposure; and yet, such little light.

Kindness, thankfully; cares not much for laws of physics. Like one of Olivia’s favourite artists, David Wojnarowicz, I was “clear empty glass,” and yet, I was continually touched by the gestures and movements of a few warm bodies, in that pristine professional landscape. Over lunch, a professor I have long admired, said that she was reading my article on the train. I’m only half way through, but I promise I will finish it. On the day of the roundtable that I had dreamed up, a friend insisted that I wear a sari, and that I not leave her side. I feel so special when I walk next to you. She said this while we were walking into a Boots to buy Compede to treat her feet; blistered by wearing the ‘wrong-but-good’ shoes. After a presentation that left me feeling as frayed as laundry on a clothes line, a friend wrote me a text. Your light shone so brightly today, I hope you can hold on to some of the goodness. A reminder, that I had more agency than I was willing to admit. Reflection was bearable, because friendship is a tender mirror.

I am writing this essay on borrowed time. In the last lap of my doctoral programme; when all my words and energies should be running towards a thesis chapter. But my heart is mostly; brokenly, wandering in Palestine. I caress the thread between my loneliness and that of a whole people. Olivia writes, “when the stress is chronic, not acute; when it persists for years and is caused by something that cannot be outrun, then these biochemical alterations wreak havoc on the body.” The country is a body; and it is tired of running. Olivia reports a restless sensation of hypervigilance, after “repeated instances of rudeness, rejection and abrasion,” which makes lonely people “restless sleepers.” The country is a tired body, and it cannot rest.

Olivia writes, “loneliness is personal, and it is also political.” I’ve been swimming since I was seven, and my mind is trained to break surface, even when my limbs begin to tremble with exhaustion. I can seem most proficient; when I’m coming apart. We all can.

It feels impossible to measure the breadth of our exhaustion; and unfair still, to perform the exacting labour of keeping the tremors from showing. The pain of loneliness, for Olivia, was compounded by the demand for “concealment, with feeling compelled to hide vulnerability, tuck ugliness away.” The Palestinian vulnerability is bursting at the seams of screens. A beautiful, brave journalist in Gaza, Bisan, writes an Instagram post about the unbearable pain in her legs from sleeping on the ground- “until when world?” Tremors are proof that there is life. And also that it is in peril.

Olivia writes, “loneliness is a city.” The city is Gaza.

I tell a friend, there are children dying. So many children. She writes back, this is a complete sentence of heartbreak.

This has been a year of heart-breaks and rejections. And I’m mostly exhausted of imagining ways of tending to them without starving my hope. A father is worried about not having enough in common with his wife of thirty-five years. A friend’s partner proposes marriage and then breaks up with her in Paris. In my country of residence, the government plans to offset increased costs of living by increasing the costs of immigrant visas. My country of birth becomes a ‘major decliner’ in a democracy report. Both countries abstain from voting on a resolution for a humanitarian ceasefire. The leaves on the poinsettia gifted to me by a close friend fall off soon after he walks away from our friendship. Forests are ablaze with the worst wildfires they’ve ever seen; they just can’t stop burning. A friend tries to convince a bureaucracy that her mother is dead. A little girl identifies her mother killed in an Israeli airstrike, by her braid.

More children are still dying.

A dear friend calls me an empathy warrior. I love her so much, I would answer to any name she calls me by. I listen closely to the terms of endearment the women in my life bestow upon me; there is caution tucked into the care. I’ve thought about empathy on loop this year; and noticed how it looms larger in its absence. For Olivia, empathy is “the capacity to enter into the emotional reality of another human being, to recognise their independent existence, their difference; the necessary prelude to any act of intimacy.” My brilliant friend celebrates my capacity to plant windows and jump over fences in order to enter the lives of those around me; and what she fears, is my incapacity to leave without an exit wound.

At first I was certain. And then I was lonely. I was so sure, that my needling despair was the cost of living the life a former self had imagined for me. Where was she now?

Loneliness clarifies what Olivia calls, “the push and pull of intimacy,” the shifting wants of “needing people to pour themselves into you and needing them to stop.” When two friends dream up a winter woodland walk with their lovers; I feel distinctly awareness of my alone-ness. The achy knob in my throat, comes not from feeling excluded; I’ve been in these woods before, but from an unbridled desire to share the emotional landscape; of walking with friends and lovers. My friend is not impressed- but you ARE part of it! Her indignation is endearing.

I know, but I’m also not, in another way. And that isn’t a lack, it's a possibility. Loneliess is a braid of gratitude and greed. Her acceptance is everything. It is at once, the bite of my loneliness and the balm to it.

For Olivia, loneliness was like feeling “hungry, when everyone around you is readying for a feast.” Deep in my loneliness, I cooked many feasts. In fact, seeing loved ones curl their limbs and ensconce themselves in crevices of my home- the shaggy, purple, heather-field of a living-room rug, the sulking twin ink-black leatherette couches, an office chair that is inexplicably always pointing a bit north- their plates awkwardly piled with food, mostly cooked in spices from a different home (and a different life), is what fed me.

I couldn’t eat, and I was grateful for friends of both kinds; the ones who didn’t notice, and those who did, but understood that the nourishment I needed, was the intimate choreography of cutlery and chatter itself.

What I cherish most about friendship as a relation, is its deftness in shattering hierarchies. There is care is both asking questions and in holding them back. There were friends who came and ate the food, and asked what went into it. They nodded as I narrated ingredients, usually shaking their heads if the list went over six items. How do you do it, I could never. Friends who thanked me profusely, and insisted on helping with the dishes. My response mirrored theirs. I could never.

There were also friends who noticed how precarious I felt, but spared me the labour of narration. A friendship without cue-cards, and yet of infinite apprehension. A friend walks in with responsibly sourced cardboard-boxes filled with unethical quantities of cheesecake. You’re already cooking dinner, dessert can be sourced. A friend sets her laptop bag down, pours water for us both and looks at me longingly from the threshold of the kitchen; voice liquid with restrained concern. How long have you been standing there? A glass of water, maybe?

It is the maybes, hanging lovingly off the edge of mouths; that kept me anchored, as I teetered dangerously close to the cliff.

The cliff of my cooking hob, and a heart with bores.

Last week, a friend and I are rejected for the same fellowship. We are each more interested in making sure the other feels accompanied. He asks me what my feelings are, and I loan a journal entry from Henry Darger, another artist I met in Olivia’s book- “This year was a very bad one. Hope not to repeat.” I mean it, and yet I don’t.

I want to wish away the rejection, but I want to keep him company. To shrug off the heartbreak, and keep the heart. Olivia wonders about the possibility of loneliness taking us “towards an otherwise unreachable experience of reality.” I wonder, if, the forcefield of my loneliness can press into others.’ If it is indeed possible to peep inside aching heart-hinges; and pour molten light into them.

If looking indeed, is the antidote to loneliness, I want to learn how to look tenderly. And I want tenderness to matter politically. Like Olivia, I don’t want to think of our estranged condition as one of prefixed failure, but to look closely, at the incessant gestures towards repair. To write of loneliness as fiercely cultivated hope, not evidence for the lack of it.

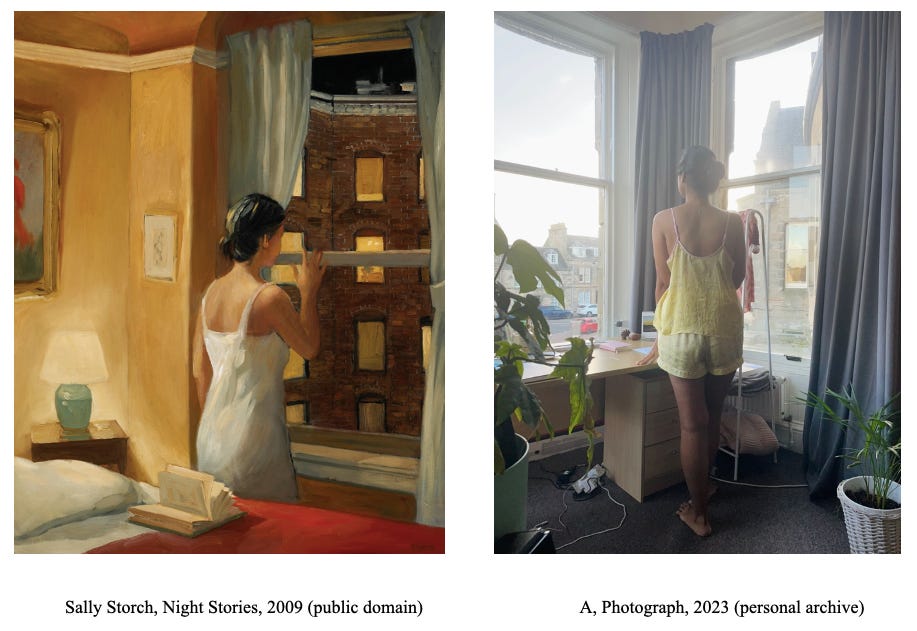

My time walking through the virtual galleries of the Hoppers, brought me to fascinating work of Sally Storch. Edward’s influence is easy to spot- in the narrative scenes of city-life, the attention to sheaves of light, and romantic shadows. Of all her paintings, there is one; Night Stories, that I couldn’t stop looking at. A woman standing by her window, in the glow of a lamp, a book fanned out on her bed. She is touching the frame of her window, and there are other windows; both lit and snuffed. An image of being in the thick of living. It feels so eerily familiar.

I am reminded of a photograph from earlier this year, taken by a friend on a September morning; my third anniversary of moving to Scotland. The photograph is largely unremarkable in how daily it is; on most mornings, I wake up and tumble down the three stairs from my loft bed, into my living room brimming with the tidal light of the North Sea, and look out of the biggest windows I’ve ever had. But next to Sally’s painting, it shimmers. It narrates an alternative story of aloneness, what Olivia calls, a slow absorption of one’s aliveness; without needing to “constantly inhabit peak states.”

The loving gaze and documentary labour of the photographer, my friend; is also a recalibration of my loneliness. A reminder of the solidarity and kindness which serrates my solitude, without slicing it. You moved countries and built a life. You can stare at the morning sky. I’m here with you.

Olivia writes of the photographer Nan Goldin; who didn’t believe in taking singular portraits, but aimed to “capture a swirl of identities over time.” I love that aim: a swirl of identities. She insisted that her photographic gaze was not voyeuristic, “I’m not crashing; this is my party.”

I want to be at each one of Nan’s parties.

To be lonely, is to be wanting. To acknowledge, in Olivia’s terms, that one is unable “to find as much intimacy as desired.” The thread between Olivia, Bisan, and Jo, is their recalibration of loneliness in the grammar of hope.

Hope is not a utopian future; it is a political refusal to accept an annihilating present. It is the very condition for imagining futures. The effort to claim loneliness as a genre for living, is to trouble what Olivia identifies as the “mainstream experience, which seems benign, even banal, its walls almost invisible until you are crushed against them.” To resist being sundered to hierarchies of pain, and the shame that comes from wanting to be touched, and not qualifying for it.

What’s shameful about wanting to be loved; in New York, in Leith, in Gaza? About wanting to care for and paint flowers? About wanting a sky that doesn't rain bombs?

I know that my loneliness has a scent; because I wore it all year. I agonised over it, worried; that I might osmotically transfer its constituent anxieties into those around me.

How to hold a body; which has only ever held other bodies? And how to do it, feeling more fish than woman? How to tell, if others could smell the inflicted shame of being alone past a socially-sanctioned age, which carried with it, per Olivia, the “persistent whiff of strangeness, deviance and failure;” as if we were living a life “so counter to the lives we are supposed to lead, that it becomes increasingly inadmissible?” Where do you file the rejections for institutions to which you did not apply?

A November afternoon; I sit in the stomach of my department building, waiting for a friend. She’s not here just now, but she will be. I can tell, because the slender glass column of her office door, is aglow from a lamp inside. It’s a friendship where we leave each other light notes. I know you’ll be early, the yellow will keep you company.

Moments later; she tumbles in, and wraps her arms around me. Hi darling, you smell great. What is that scent?

I smile. It’s something citrusy.